Exercises

Below are the instructions for a study that we recently wrote up in a paper entitled "Working towards the experimenter: Reconceptualizing obedience within the Milgram paradigm as identification-based followership". The study's goal was to see whether the process of social identification with tyrannical leaders that we suggest is implicated in participants' willingness to act tyrannically in a prison setting might also explain participants' behaviour in Stanley Milgram’s obedience to authority research.

The instructions are very long, but we have reproduced them here so that readers of our paper can work through the procedure themselves — or incorporate them into a teaching exercise.

______________

Instructions

In Milgram's research, members of the public participated in what they thought was a memory experiment, conducted by an experimental scientist.

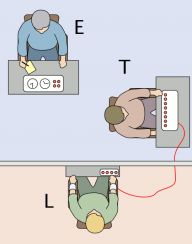

The scientific cover story indicated that the purpose of the study was to investigate the effects of punishment on learning. In the studies themselves, the participant was cast in the role of teacher (T) and another person (actually a confederate of the experimenter) was cast in the role of learner (L), while the study was overseen by an experimenter (E, another confederate) The learner had to learn a series of word pairs, and the teacher’s job was to administer electric shocks of increasing magnitude to this person when they made an error.

Below, we describe one of the best known studies in this research programme, followed by 15 variants that involved the same paradigm. Your task is to make some judgments of these different variants. In particular, please indicate to what extent the experimental set-up would incline participants to identify with different parties in the experiment.

More specifically, for each variant, please indicate the extent to which you think that the set-up would incline participants:

(a) to identify with the experimenter as a scientist and with the perspective of the scientific community that he represents, and

(b) to identify with the learner as a member of the general public and with the perspective of the general community that he represents.

As a starting point for this exercise, consider the basic study that Milgram describes in his 1974 book Obedience to Authority. In this, the experimenter is in the same room as the participant (the ‘teacher’), and the ‘learner’ is in an adjacent laboratory where he cannot be seen. As the task progresses, the learner is administered shocks (because he starts to make errors), and he is heard to utter a series of complaints that can be heard through the wall of the laboratory.

To anchor future judgements, let us say this in this variant identification with the experimenter as a scientist is high and judge this to have a value of 80 on a scale from 0 to 100. Let us also say that in this variant identification with the learner as a member of the general public is moderate and judge this to have a value of 50 on a scale from 0 to 100. This, then, would lead to the following responses:

Identification with E & science 80 Identification with L & community 50

When reflecting on the remaining variants — which are described below — your task is to make similar judgements using these values as a benchmark. In other words, you should consider whether the variation in question would increase or reduce identification with the experimenter and with the learner, and indicate values accordingly.

This is a task that you can do on your own but it may also be interesting to do in a group.

The variants

Note: T = Teacher (the participant), L = Learner (a confederate), E = Experimenter (a confederate).

v1. L Remote Feedback. No vocal complaint is heard from L who is in another room where he cannot be seen. But at 300v he pounds on the walls in protest.

Identification with E & science _ _ Identification with L & community _ _

v2. L Voice Feedback. Identical to v1, but L’s complaints can be heard clearly through the walls of the laboratory.

Identification with E & science _ _ Identification with L & community _ _

v3. L Proximal. Similar to v2, except that L is in the same room as T, a few feet away. L is thus visible as well as audible.

Identification with E & science _ _ Identification with L & community _ _

v4. L Touching. Identical to v3, but L receives a shock only when his hand is on a shock plate. At 350v level L refuses to place his hand on the shock plate. E orders T to force L’s hand onto the plate.

Identification with E & science _ _ Identification with L & community _ _

v5. New Baseline. Study moved from elegant Yale Interaction Lab to more modest basement. L responds not only with cries of anguish, but remarks about a heart problem (at 150v, 195v & 310v). This is standard in all subsequent variants.

Identification with E & science _ _ Identification with L & community _ _

v6. New Es. To speed up running studies, new E and L introduced. Previously E was hard-faced and L soft; now E soft, L hard-faced.

Identification with E & science _ _ Identification with L & community _ _

v7. E absent. After giving initial instructions, E leaves lab and gives instructions by telephone.

Identification with E & science _ _ Identification with L & community _ _

v8. Women. In v1 to v7 Ts are all male. Here Ts are women (but E and L are still male).

Identification with E & science _ _ Identification with L & community _ _

v9. Limited contract. In v5 T and L sign a release stating: “In participating in this experimental research of my own free will, I release Yale University and its employees from any legal claims arising from my participation”. When signing this L says he has a heart condition and that “I’ll agree to be in it, but only on condition that you let me out when I say”.

Identification with E & science _ _ Identification with L & community _ _

v10. Non-university site. Lab moved to an office building in a nearby industrial city, Bridgeport. Study involves no visible tie to the university.

Identification with E & science _ _ Identification with L & community _ _

v13. Ordinary man as E. E is called away, and an ordinary man, who appears to be a participant (but is a confederate), takes over his role and comes up with the idea of increasing shocks each time L makes a mistake.

Identification with E & science _ _ Identification with L & community _ _

v15. Contradictory Es. When T arrives at the lab he is confronted with two Es (E1 & E2) who give instructions alternately. At 150v E1 gives usual command but E2 gives T the opposite instruction.

Identification with E & science _ _ Identification with L & community _ _

v16. E as L. As in v15, T confronts two Es. However, at the outset, while the two Es are waiting for L he phones to cancel. Es then flip a coin to decide who will be new L. Study proceeds as in v5.

Identification with E & science _ _ Identification with L & community _ _

v17. 2 Peers rebel. T is placed in the midst of two peers (acting as fellow Ts) who defy E and refuse to punish L against his will.

Identification with E & science _ _ Identification with L & community _ _

v18. Peer shocks. The act of shocking the victim is removed from T and placed in the hands of another participant (a confederate). T performs subsidiary acts which contribute to progress of the study but remove him from the act of pressing the switch on the shock generator.

Identification with E & science _ _ Identification with L & community _ _

___________

Analysis

Now that you have done this, we can look at the extent to which your estimates of the level of identification that each variant would induce predicts the percentage of participants who were prepared to administer 450-volt shocks in Milgram’s own research. You can do this by plotting your (or your group's) responses (or the average of your responses and those of others) on the graph below. Plot values for identifcation with the Experimenter (i.e., iE) in red, and values for identifcation with the Learner (i.e., iL) in blue.

Here the black line plots the percentage of participants who were prepared to administer 450-volt shocks in Milgram's research. Our analysis predicts that estimates of iE will follow a similar pattern (so that the red line is high on the left and low on the right) and that estimates of iL will follow go in the opposite direction (so that the blue line is low on the left and high on the right).

.jpg)

Is this what you found? If so (or if not), what are the implications of this?

Our findings — based on average estimates of 32 expert social psychologists and 96 psychology students — lent strong support to these predictions. Specifically, for both experts and non-experts, there was a strong and significant positive correlation between iE and the level of obedience displayed in each variant (experts, r = .75; non-experts, r = .78), whereas there was a strong and significant negative correlation between the level of obedience and iL (experts, r = -.51, non-experts, r = -.58).

We interpret these results as supporting the idea that obedience in the Milgram paradigm is a reflection not of 'blind obedience' (as researchers typically argue), but rather of participants' identification with the experimenter and the scientific enterprise he is leading. Further details are provided in the paper which is available from the authors.

Reference

- Reicher, S. D., Haslam, S. A., & Smith, J. R. (2011). Working towards the experimenter: Reconceptualizing obedience within the Milgram paradigm as identification-based followership. Manuscript submitted for publication.